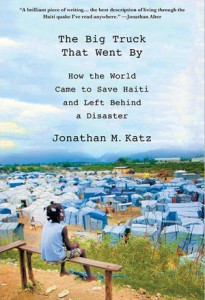

Book Review: The Big Truck Went By - How the World Came to Save Haiti And Left Behind a Disaster

Below is a review, from Reason, of Jonathan Katz's book on the shortcomings of the international community's efforts to "save" Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. While no response to the aftermath earthquake, no matter how well-organized or well-resourced would have been sufficient, he emphasizes that the subsequent reconstruction effort was hobbled by a top-down approach that excluded governmental institution, weak as they may have been, local firms, and community groups. To read an excerpt or purchase the book, take a look at Amazon.

Below is a review, from Reason, of Jonathan Katz's book on the shortcomings of the international community's efforts to "save" Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. While no response to the aftermath earthquake, no matter how well-organized or well-resourced would have been sufficient, he emphasizes that the subsequent reconstruction effort was hobbled by a top-down approach that excluded governmental institution, weak as they may have been, local firms, and community groups. To read an excerpt or purchase the book, take a look at Amazon.

Jonathan M. Katz begins his book about the devastating Haiti earthquake of 2010 with men pulling children from the rubble of a collapsed Port-au-Prince school called La Promesse. In efforts to save on construction costs, the school’s owner had done what many in the city do: He had used thinly mixed concrete and skimped on rebar. When the three-story structure collapsed into the ravine beside it, nearly 100 schoolchildren died. The collapse happened in 2008, two years before the earthquake that destroyed more than a hundred thousand structures in and around the Haitian capital and killed anywhere from 85,000 to 316,000 people. It was a spontaneous implosion. Katz, a reporter with the Associated Press, asked then-president René Préval why a building code wasn’t in place to prevent the school collapse. Préval replied that there was in fact a safety code, but the owner had failed to follow it.

The institution intended to prevent such catastrophes existed but wasn’t effective. In The Big Truck That Went By, Katz presents an engaging first-person account of the quake and the first year of the international response that followed. He recounts living through the earthquake in the AP house, which served both as his residence and as an office for himself and his Haitian fixer/driver/translator, Evens Sanon. The first chapter takes readers through the chilling hours that followed the quake as Katz and Sanon rode around a devastated Port-au-Prince trying to apprehend the destruction and find a cell signal to file reports. “For decades,” Katz writes, “researchers have told us that the link between cataclysm and social disintegration is a myth perpetuated by movies, fiction, and misguided journalism.” His experience after the quake rebuts such myths. While “the quake zone would be seen as a helpless zoo” to those overseas, Katz says that there “was no sign of violence....In the midst of near-total disaster, people were trying to go on.” All the people panicking, he writes, were outside the country.

A few days after the earthquake, for example, Katz and Sanon traveled to Léogâne, a town just west of Port-au-Prince and near the quake’s epicenter. As they approached the town’s limits, they come upon a barricade and group of young men wielding machetes and clubs. They were, Katz learned, “on guard for bands of looters they heard were running wild in the capital.” “Where did you hear that?” Katz asked. “On the news,” came the reply. Léogâne was mostly peaceful, if mostly flattened. The factors that fueled panic abroad were some of the same ones that have made it difficult for outsiders to effect progress in Haiti, a theme underlying Katz’s account. Language and cultural barriers generated misunderstandings. The perception of a “helpless zoo” led to an immediate foreign response that was overly focused on security—it included 22,000 U.S. Marines—at the expense of other priorities. It also helped ensure a “command-and-control” approach to disaster releief, which Katz says limited responders’ geographic focus. The “top-down, highly centralized model,” he writes, “as opposed to a broader-based, collaborative approach, meant that parts of the capital such as Pétionville received tremendous amounts of attention while outlying areas such as Carrefour were ignored.”

The inherent divisions between outsiders, known as blan in Haitian Creole, and Haitians meant “many organizations took measures fit for a war zone, curfews and tight restrictions on what neighborhoods staff could enter.” Crime wasn’t nonexistent, but the reaction was far out of proportion to the risks. This “Blan Bubble,” Katz writes, in which he and all foreign journalists, aid workers, and diplomats operate, affected the first few months of relief response. But that was just the beginning. “The problem was that these individuals were merely the vanguard of distant, massive organizations whose managers seemed less interested in nuances or painful lessons on the ground. And their—our—ability to report back those nuances was inhibited by the fact that we were viewing life through a bubble, separated by language, class, and divisions that stretched back farther than Haitian history.” He describes how these divisions led to short-term or supply-driven aid approaches that amounted to applying band-aids rather than helping to improve (or build anew) local institutions. He also acknowledges that outsiders operating with limited local, language, and cultural comprehension aren't very well-equipped to effect that change in the first place. At one point, Katz compares Bill Clinton, the U.N.’s special envoy to Haiti since 2009 (dubbed Le Gouverneur by the Haitian press), to the Protestant missionaries who have been coming to Haiti since the 19th century with the conviction that “only an outside force could save Haiti.” International media coverage helped private U.S. donations reach $1.4 billion by the end of 2010. That media onslaught involved many foreign journalists who swarmed into Haiti for the first time while covering the disaster. Superficial reporting, Katz notes, at times reinforced perceptions of corruption in the Haitian government that may not have been warranted, as when reporters repeatedly citied Transparency International’s index about perceived corruption as if it were God’s law.

Katz doesn’t claim that the Haitian government is a bastion of purity and transparency. But he does make a case that overblown perceptions about corruption led to an unwarranted degree of mistrust. These perceptions make donors reluctant to funnel money through Haitian entities, governmental or not. It has even led some to consider freezing aid to Haiti altogether. Katz also claims that observers unfairly hold Haiti to a different standard than, say, the United States, documenting several questionable purchases that Americans bought with Haiti aid money: $368,000 in food and lodging for U.S. government employees at the five-star Mandarin Oriental hotel in Washington, D.C.; $4,462 on a deep fryer for the U.S. Coast Guard. Ultimately, foreign governments and agencies like the World Bank pledged billions to rebuild Haiti, but much of the promised aid has yet to be delivered, and most aid that has been spent went to foreign aid groups and contractors. Donors have channeled comparatively minuscule amounts to the admittedly weak Haitian government and local firms and organizations, the parties Katz advocates should receive a larger share of the pie. These local entities are presumably most interested in “the need to build strong, well-funded institutions” that President Préval preached in the aftermath of the quake. Katz may be overly optimistic about channeling aid through Haiti’s government. But Haitian businesses and civic organizations have the local context required to work in the country nimbly and effectively, and they have the greatest incentives for better institutions to develop.

Katz’s account offers evidence that international efforts after the quake have failed to push Haiti very far toward reconstructed housing, let alone better institutions. After the 2008 school collapse, Préval told Katz that “political instability” is what keeps Haiti from realizing institutions that preclude disasters like La Promesse. Once stability arrived, the president claimed, progress would follow. Katz’s follow up question to Préval two years before the earthquake is the one that remains today: “But what will you do until then?”

Add new comment